DIED.

In this town, on Monday last, Thomas Dugan,

alias Ward, a colored man, aged about 80.

He was formerly a slave to a Mr. Soloman Ward

in Virginia, whence he absconded about

40 years since; and has since resided in this town.

— Yeoman’s Gazette, May 12, 1827

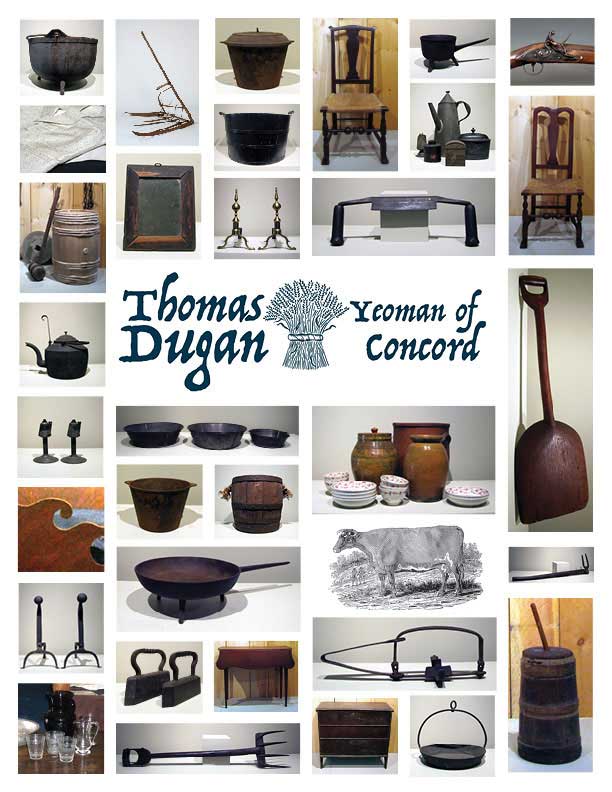

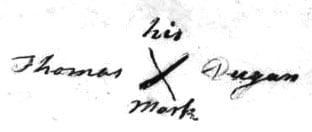

Thomas Dugan (1747-1827) was born almost thirty years before the start of the American Revolution and was enslaved in Virginia. We do not know how he came to be free, but he arrived in Concord by about 1791 and lived as a free man for the rest of his life. While the beginning of his life is undocumented, by carefully studying his probate inventory, we can catch a glimpse into his life in Concord. Thomas Dugan’s probate inventory is a particularly rare survival because it is a primary source detailing the material possessions of a free black man in early 19th-century Concord.

Dugan is referred to as a yeoman on the inventory of his estate; a yeoman is a property-owning farmer. The value of his property indicates that Dugan was a good farmer; he was a land owner—fewer than half of his Concord contemporaries, white or black, could say the same—and he died without any debts, rare at the time when surviving on credit was normal. Long after he died he was recalled as an expert grafter of apple trees, one who “did much to advance the farming interests in Concord; he was industrious and a peace maker.”

This on-line exhibition brings together a selection of the material from a special exhibition on view at the Concord Museum from May 15, 2015 through May 1, 2016 and expands on the resources available to learn more about Thomas Dugan and his Concord contemporaries.

To view images or videos, please click on the images below.

Visit The Robbins House in Concord, revealing the little known African American history of Concord and its regional and national importance.

Explore Boston’s Museum of African American History.

Discover the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D. C.

Background photo: Probate Inventory of Thomas Dugan, 1827

Photo/film credits: David Bohl; Six One Seven Studios. The video was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Primary Source Evidence

Probate inventories are valuable documents that provide a snapshot of a household at a particular moment in time. Probate inventories were taken when a property owner died in order to determine the value of the possessions they left behind—land, buildings, furnishings—to fairly distribute the property to heirs and to settle debts. For historians and curators, this information can be useful when researching people who are difficult to find in other sources of recorded history.

However, because not all household items were listed on inventories, the snapshot is almost always incomplete, and there is no reliable formula for determining what may be missing. Inventories nevertheless can give us a compelling view of daily life in a household.

Thomas Dugan’s inventory is a particularly rare survival because it is a primary source detailing the material possessions of a free black man in early 19th-century Concord. It provides an opportunity to learn more about his life, his family, and his town in 1827.

Preview the book, Black Walden: Slavery and Its Aftermath in Concord, Massachusetts, by Elise Lemire.

Uncover the stories of the occupants of The Robbins House in Concord, some of whom were contemporaries of Thomas Dugan.

Connect with Concord’s farms today.

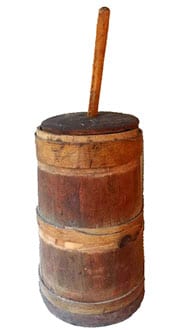

Top image: A selection of objects from the Concord Museum collection similar to those listed in Thomas Dugan’s probate inventory

Background image: Thomas Dugan’s Probate Inventory, 1827

Film credits: Six One Seven Studios. The video was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

What's Missing?

Thomas Dugan died testate—having created a will. He left his estate to his “beloved wife Jenny Dugan,” with $1 each to three sons and two daughters, and $10 each to his two youngest sons.

Thomas Dugan’s probate inventory gives us a sense of his life through the belongings listed. Even with a list like this, there are likely items missing. There is no way to know what was not recorded by the appraisers of his estate – objects of sentimental value, but no monetary value, for instance, may have been excluded.

Where is the clothing belonging to his wife and children? Did they own any books? Most inventories list the food stored in the house; there is no food listed in Dugan’s inventory. Where is the plow? Dugan may have borrowed a plow from neighbors or it may be possible that with only seven acres, most of which probably grew grass and hay for the cow, Dugan did not need a plow.

Despite what may be missing, the inventory still provides a glimpse into Thomas Dugan’s life that would otherwise not be possible. It also can give us a sense of the lives of his contemporaries who are otherwise invisible to history.

Thomas and Jenny Dugan’s son, George Washington Dugan, enlisted in the Massachusetts 54th in 1863 and was officially listed as missing in action after the attack on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. His name, however, is missing from the Civil War monument in Concord Center. Visit the National Archives to learn more about black soldiers in the Civil War.

Elisha Dugan,—O man of wild habits…Elisha Dugan, son of Thomas and Jenny Dugan, is remembered in a poem “The Old Marlborough Road” by Henry Thoreau, published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1862.

The names of streets are often a lasting reminder of a town’s early history and are expressive of the personality of the town. Jennie Dugan Road in Concord is named for Thomas Dugan’s wife, whose name was also spelled Jenny. The Dugan home (no longer standing) was off Old Marlboro Road, near today’s Jennie Dugan Road.

Background image: Thomas Dugan’s Probate Inventory, 1827

For Teachers and Students

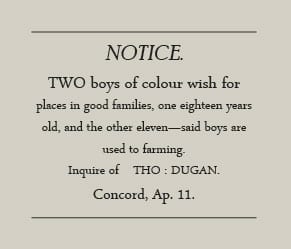

The exhibition Thomas Dugan: Yeoman of Concord was a visualization of one man’s belongings based on a primary source – an inventory taken after Dugan’s death in 1827. The inventory, along with an obituary, a newspaper ad, and Dugan’s will, are a few remaining written records by which we can piece together parts of Dugan’s life. Most of Dugan’s contemporaries left no written records at all. And yet, by scouring the primary sources we do have, using historical objects as primary sources in their own right, and looking at history through different lenses, we can learn a great deal about the daily life of an African American farmer in Concord in the 1820s.

This page provides resources to learn more about Thomas Dugan’s inventory, African American history in Massachusetts, and probate inventories as primary sources. For teachers, there is information and a lesson plan to use Dugan in the classroom.

Thomas Dugan’s Inventory

Explore this detailed look at the objects included in Thomas Dugan’s inventory. Download Inventory

Lesson Plan

Thomas Dugan: An African American Life in 1820s Concord

Created with students in the Rivers and Revolutions program at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School, this lesson can be used in the classroom and is aimed at US History Courses. This discussion-based, virtual field trip will help students investigate the life of one man who died in 1827 through the objects listed on the inventory taken at his death. The activities are designed to work well for visual learners, provide opportunities to use both object-based learning and primary sources as historical evidence, and help students connect to historical objects that real people have left behind.

Topic connections: life in the early 19th century; post-Revolution and pre-Civil War units; African American history; lives of people who were formerly enslaved; daily life for the middle class.

- Download Lesson Instructions

- Download Lesson Slideshow

- Download Lesson History and Approach

- Download Student Worksheet: Thomas Dugan Inventory

- Download Student Worksheet: Obituary

- Download Annotated Inventory

For more teacher and student resources visit our Education pages.

Explore how to use probate inventories in the classroom.

Learn more about the lives of African Americans in Massachusetts after the end of slavery through historical manuscripts and rare published works from the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Go for a walk! The Robbins House has developed a self-guided trail map of African American and Anti-slavery history in Concord.

Background image: Thomas Dugan’s Probate Inventory, 1827

Collaborative Partners

WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO

for their collaboration on the special exhibition

and on the videos on this website.

And to the exhibition’s Advisory Group

Nancy Butman, Liz Clayton, Anne Forbes, Jayne Gordon, Robert Gross,

John Hannigan, Maria Madison, Rob Morrison, Linda Ziemba

and also to

Judy Fichtenbaum, Jonathan and Judy Keyes, Sara Lundberg,

John and Lili Ott, Lawrence O. Sorli,

and the students and teachers of Rivers and Revolutions

at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School

Background image: Thomas Dugan’s Probate Inventory, 1827